Can You Hear Me Now?

/Here’s a short – one question - quiz: What is the most important skill that a mediator brings to a mediation? The answer: The willingness and the ability to actually listen.

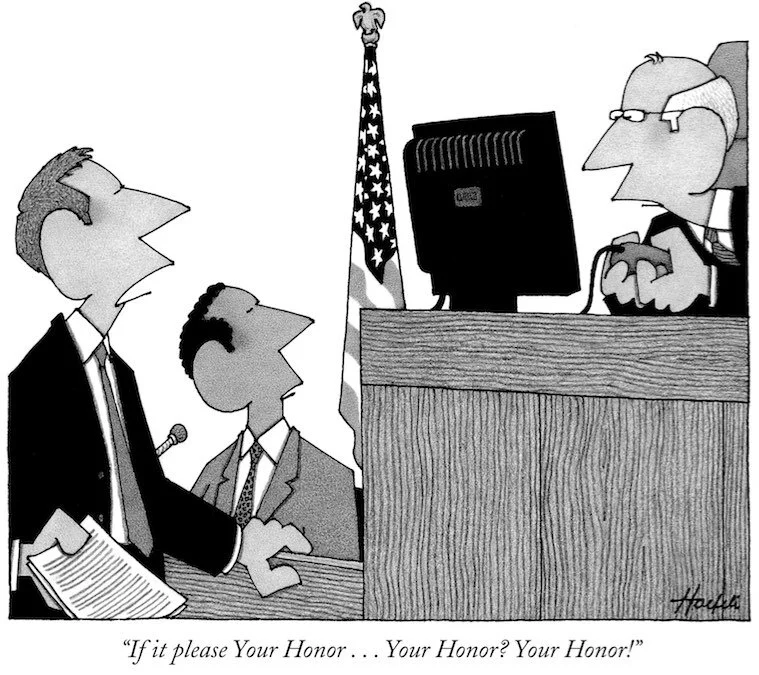

In this political season, we are offered endless, graphic examples of people unable or unwilling to listen to each other. Talking heads are everywhere. In our personal lives, the signs are impossible to ignore; people not making eye contact with you, looking at their “smart” phones while you’re talking (and sometimes while they are talking), interrupting you mid-sentence or answering a question in a way that makes perfectly clear that they did not listen to a word you said. We place a high value on skill at employing technology to communicate, whether it is on TV, a TED talk, a podcast or in a tweet. None of it involves listening. We have far more experience feeling isolated and misunderstood than we do feeling heard and understood.

What, then, is it when a mediator actually listens? It is more than just hearing what someone says. In her recent New York Times Opinion Piece, Kate Murphy says that “[I]t (listening) also involves paying attention to how they say it and what they do while they are saying it, in what context, and how what they say resonates within you.”[1] It is also more than imitating a potted plant while someone else is talking. Again, to Kate Murphy’s essay: “A lot of listening has to do with how you respond – the degree to which you facilitate the clear expression of another person’s thoughts and, in the process, crystalize your own.” [2]

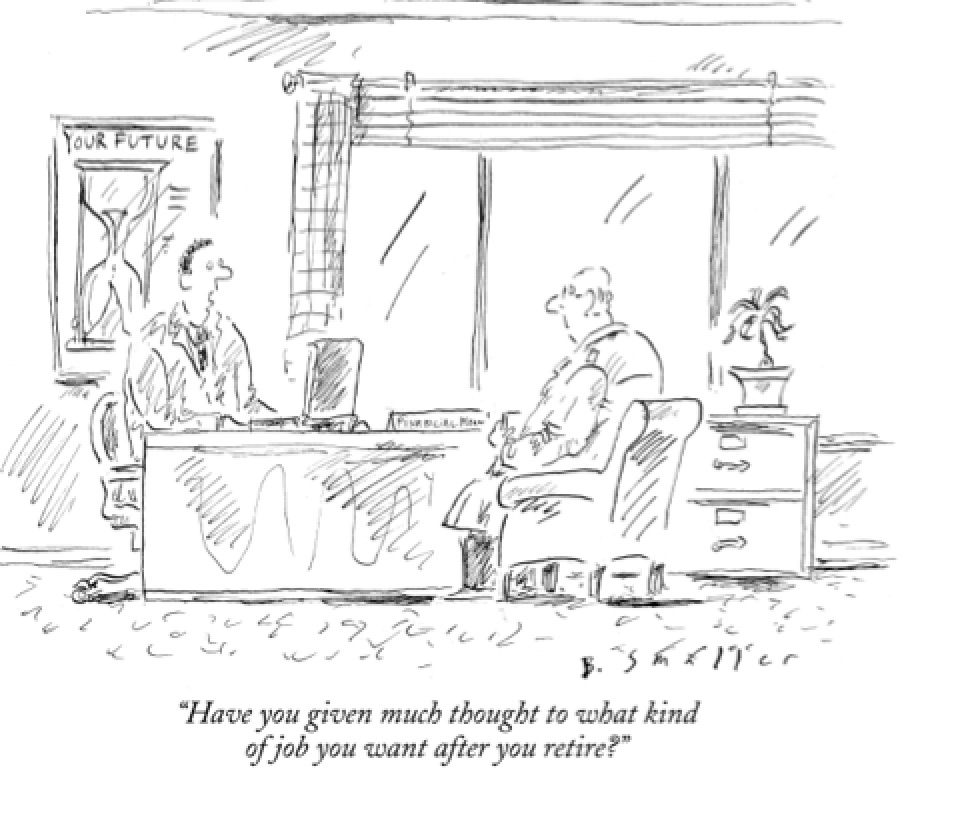

And that leads, inescapably, to the other critical skill you should expect from a mediator who is a good listener – the willingness and ability to ask good questions. If a mediator sees his or her role as getting the case settled then the questions will be designed to support and advance the mediator’s view of the case. If, on the other hand, the mediator is actually curious about what he has heard after engaging with and listening to the parties, then the questions will not have “the hidden agenda of fixing, saving, advising, convincing or correcting.”[3] A mediator who listens is also less likely to assume that he or she already knows what the other person is going to say. In fact, a mediator who is an attentive listener often receives more information, relevant details and elaboration from the mediation participants than by asking pointed questions. That information and those details are the building blocks for a successful mediation.

[1]Murphy, Kate. “Lessons in the Lost Art of Listening.” The New York Times, January 12, 20020 www.nytimes.com/2020/01/09/opinion/listening-tips.html

[2]Ibid.

[3]Ibid.